Offline Methods

Mixed qualitative and quantitative data-intensive approaches were taken to the analysis as appropriate to the data. For the offline rapid ethnographic research (including interviews, observation and participatory visualisation/mapping), analysis involved close reading and qualitative analysis of concepts, themes and discourses.

The sections below provide an introduction to individual methods, explaining what they involve, why you might use them, and how they can be used. There are also short videos on each method by Professor Siân Jones and Dr Liz Robson. To see what kind of results can be achieved using these methods, please take a look at the PRACTICAL EXAMPLE section (Woolwich, Canongate, San Donato). Furthermore you can find the case studies reports in the Participatory Methods RESOURCES page.

Observation

Dr Liz Robson explains the Observation method

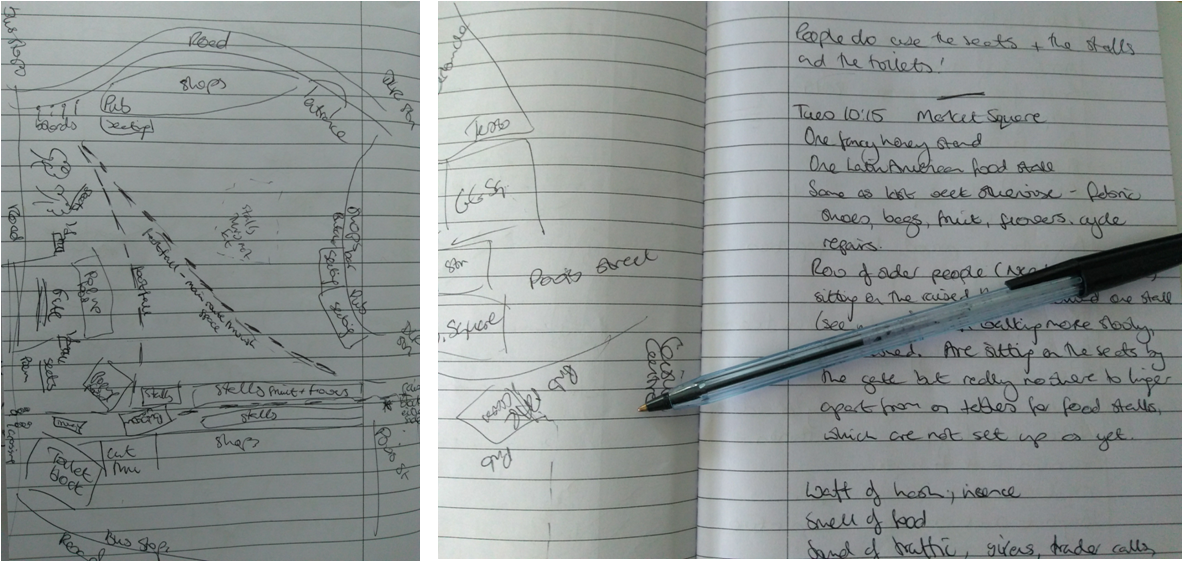

Observation is based on structured time spent at the place of interest, paying close attention to who is present and what is happening. What is seen and felt through other senses is recorded using notes, images, or a sketch map of the area. Observation is normally conducted over multiple sessions, to allow for comparison and to understand how places change at different times. Observation can also include noting evidence for uses of the space that might be harder to directly observe, such as those taking place out of hours, at night, or unsanctioned activities.

Observation can provide valuable insights into patterns of behaviour: who is present at a site, when, and how they are using the space. These insights can be a useful basis for developing interview questions and determining which participatory methods might be most appropriate to pursue (and with which groups).

As a non-participatory method, it is within the observer’s control when and where they conduct observation. However, it may be necessary to seek consent from officials for the activity and it is important to make people aware that observation is taking place, especially if you are in a private or semi-private space.

For example, using observation in the Beresford Square, Woolwich case study helped to identify how patterns of use changed depending on the presence of the market traders and revealed how people were engaging (or not) with the Royal Arsenal Gatehouse as they moved through the space. Both these aspects were picked up in interviews and explored through the participatory mapping.

For further details: https://socialvalue.stir.ac.uk/methods/observation/

Left: Behavior mapping sketch Beresford Square Right: Behavior mapping notes Beresford Square ©Liz Robson

Interviewing

Professor Siân Jones explains the Interviewing method

What are interviews?

Interview is very widely used in qualitative social research. This method involves asking participants a series of questions (usually between 5 and 15), in a one-to-one conversation, or sometimes in pairs or groups (also known as ‘focused group interviews’). Importantly, the questions are open-ended, allowing participants to answer in their own words, in contrast to closed responses (tick boxes), which are typically used in questionnaire surveys. Interviews can be more or less structured, and we explain different types of interviews below. They are often conducted in person but can also be done by videocall or phone. They are also recorded in some way for the purposes of analysis, usually by audio-recording or sometimes using detailed notetaking. Analysis typically focuses on identifying themes and dissecting the language used to describe things, in order to understand implicit meanings, values and relationships as well as explicit ones.

Why would you use them?

The interview method is useful for understanding participants’ thoughts, experiences and values, because they can elaborate on these from their own perspectives and the interviewer can ask follow-up questions to clarify and explore topics further. We used interviews to gain depth of understanding about the social values associated with the ‘deep city’ by asking people what specific historic layers of the city mean to them, if anything. Interviews also allowed us to gain a holistic understanding of how the ‘Deep City’ informs people’s sense of identity and place, as well as its place in their everyday lives. Through interviews we were also able to explore their attitudes to change, including past and future development planning and regeneration. The knowledge and understanding produced by semi-structured interviews are to some extent co-produced by the researcher and participant. Even though the researcher designs the opening questions, the conversation that ensues is strongly informed by the participant’s responses, creating a more equal and reciprocal relationship (especially in the case of the semi-structured interview and the participant-led walking interview, see below).

How are they used?

We recommend three types of interviews as part of the Deep Cities toolbox:

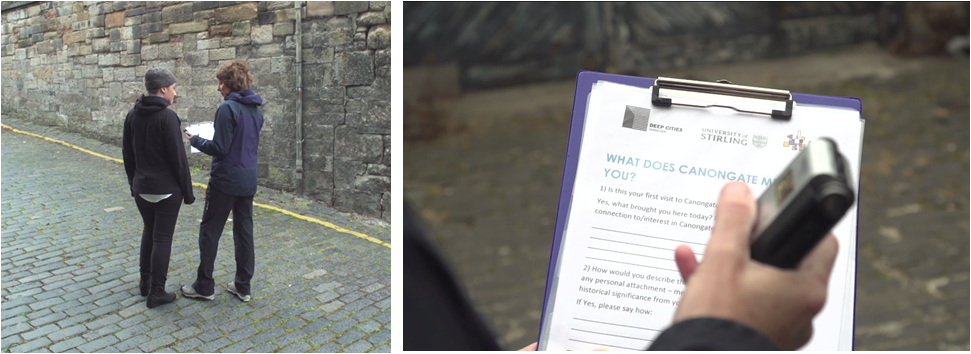

Structured interviews involve a series of pre-determined questions asked in a structured manner, in sequence, and with fewer, if any, follow-up questions. The method is more like a spoken questionnaire, but with open responses that allow for qualitative analysis. It is a more standardised method, but also generally shorter (c. 10-20 mins) and suitable for use when recruiting and interviewing people in the street or in other urban spaces.

Semi-structured interviews allow for more depth of discussion and exchange and require greater investment of time from participants (c. 30-90 mins). The researcher prepares some starting questions for the topics they wish to discuss, but these are not always asked in the same way or in the same sequence. Follow-up questions or prompts are used to probe topics in more depth, following the flow of the conversation to explore unanticipated and new directions.

Walking interviews involve interviewing a participant about a place whilst walking though/around it. This kind of interview is particularly useful for understanding people’s responses to specific features of the ‘deep city’. The interview can be ‘participant-led’ with the interviewer asking the participant to take them on a typical walk and/or to focus on features in the urban built environment of relevance to them. A more structured approach (sometimes called a ‘transect survey’) is when the researcher identifies the route and asks each participant to follow this, discussing features along the way.

Semi-structured and structured interviews can be used in the same project. Semi-structured interviews provide more in-depth understanding and can be used with key-stakeholders, but structured interviews are shorter and are better when recruiting and interviewing people in situ in specific urban locales. The latter approach can be useful if it proves difficult to access residents and workers in other ways. As a method, the interview can complement observation in specific locales, helping the researcher to understand the behaviours they have observed. Semi-structured interviews can also be followed by a walking interview, or the walking interview method can be used independently.

Participatory Mapping

Dr Liz Robson explains the Participatory Mapping method

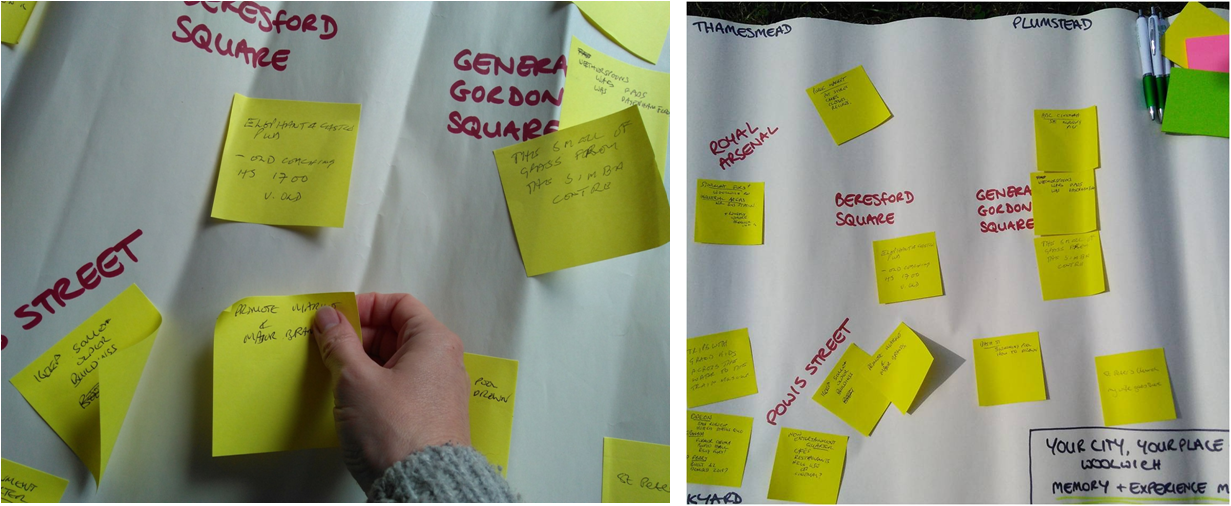

Participatory mapping is a creative method that can be used with individuals or in groups. The maps can contain anything participants choose, combining what happens at different times, multiple senses, and movements or connections between places. Maps may be drawn or comments added to a pre-existing template, but they do not necessarily need to correspond to a geographical representation of the space. Discussion with participants is therefore critical, in order to understand the resulting material.

Participatory mapping can reveal the aspects of a place that are especially important to people through memories, feelings, practices, and associations. The maps can be useful inputs to other group discussions and can challenge taken for granted understandings of a space. Cumulative or group maps also allow multiple values and voices to be visually represented in a single image, reflecting co-existing diversity and difference.

Where and how the mapping activity takes place will impact on the knowledge generated. It may be desirable to conduct the mapping at the site of interest, to gather immediate, multi-sensory responses; or to facilitate participation through linking-up with an established community activity or space; or to focus on a cumulative or group mapping in order to see how differing values are negotiated. As a participatory method, these decisions will likely be a balance between what is practical (when and where people are willing and able to participate) and the questions being addressed through the exercise.

In the Beresford Square, Woolwich case study, a cumulative map was produced by participants (contributing individually and in small groups), who placed post-it notes on an outline map of the area. This activity was held at a community-led gathering away from the Square, in order to involve a range of people who had not been engaged through interviews, with different demographics and from multiple generations. The process resulted in a diversity of places being identified as of significance and prompted discussion among participants about their memories.

For further details on this method and other examples of participatory mapping being used in practice, see: https://socialvalue.stir.ac.uk/methods/mapping/

NB Participatory Mapping can also take place online. See Crowdsourcing in the ONLINE Methods page

Photo Elicitation

Photo elicitation uses images as prompts for discussion. The images might be historical or recent, provided by the researcher or provided/taken by the participants. While the images chosen should relate to the place of interest, participant responses will not necessarily correspond directly with what is depicted.

Images can provoke a range of emotional and reflective responses – they may be used by participants in constructing their own narratives of place, to draw parallels to their own experiences, used to highlight how places have changed (including noting absences in the images or what is not captured), or to identify aspects of continuity and familiarity. The emphasis is on understanding the participant’s response to an image.

The photo elicitation method is dependent on discussion and often combined with other forms of interview. When used in group situations, it can encourage people to share and discuss their differing memories and values. The creative, visual element can help engage otherwise more reticent participants and open-up new avenues for enquiry.

For example, in the Canongate, Edinburgh case study, photo elicitation was used in interviews and in a group discussion. The images helped draw people into the conversation and were used to connect the history of the site to their present-day experience of place. While photo elicitation uses photographs as prompts, other types of audio-visual material can also be used in similar ways. In one interview, an (externally developed, pre-existing) virtual 3D tour of the interior of the Old Tollbooth Market was shown to an individual familiar with the recent use of the space. This prompted them to share their memories and what they knew about the history of different parts of the building; a degree of detail that, without access to the interior of the site, was difficult to obtain through other engagements.

Photo elicitation in Canongate, Edinburgh Case Study ©University of Stirling

Ethical guidelines for the offline methods

- Association of Social Anthropologists of the UK and the Commonwealth https://www.theasa.org/ethics/

- Research Ethics Framework (REF) authorised by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC): ESRC Research Ethics Framework

For further information about qualitative social research methods see the Social Value Toolkit, which was developed to help guide heritage practitioners who need to understand the social values associated with the historic environment as part of their work. This was developed by Dr Elizabeth Robson, one of the Deep Cities Researcher, as part of a collaborative doctoral project supervised by Professor Siân Jones, a Co-Investigator for the University of Stirling Deep Cities team responsible for WP3. The collaborative doctoral project and Social Value Toolkit is the result of a collaboration between University of Stirling and Historic Environment Scotland, and was jointly funded by these organisations

Dr Elizabeth Robson, University of Stirling, Historic Environment Scotland

Last update

09.01.2023