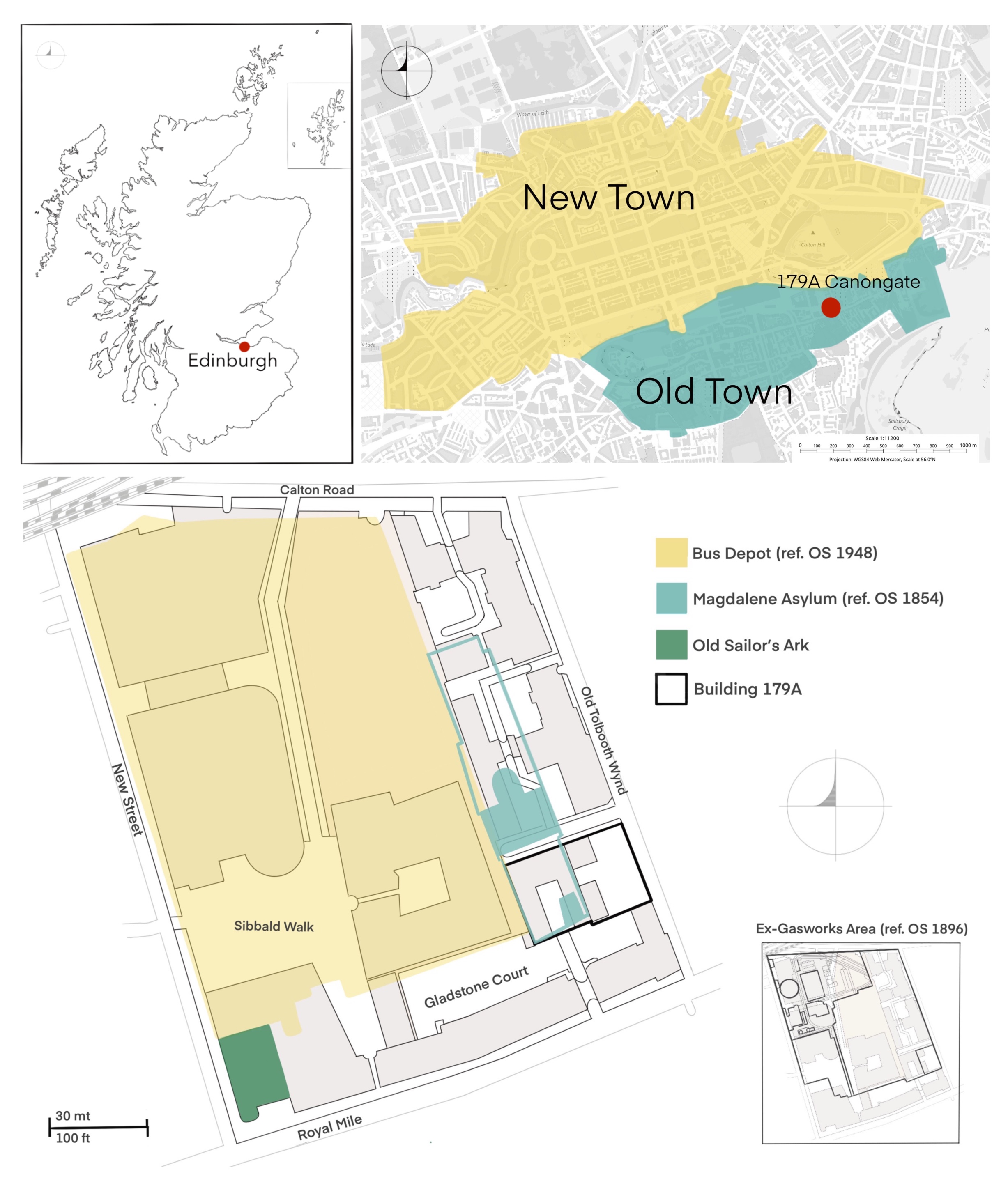

Edinburgh, UK

HERITAGE AND PLANNING IMPLICATIONS

Location

The case study focused on an area of North Canongate, Edinburgh, occupied in the 19th century by the New Street Gasworks and its final expansion into the location of Gladstone Court (179a Canongate). This site represents the last upstanding remains of the Gasworks, which had been re-used as art gallery, architect offices and, recently, as an entertainment venue and alternative market. However, at the time of our research they were standing empty awaiting an approved redevelopment for student accommodation, which will see most of the structures demolished, except for selected facades.

Originally based on the contested Caltongate masterplan, the redevelopment of the area was rebranded as the prestigious New Waverley development in 2014. Heritage has been mobilised by campaign groups contesting both the Caltongate and New Waverley development plans, in a context in which tensions revolve around the prioritisation of civic infrastructure and developer wishes versus residents’ desire for community spaces. Our choice of this case study was influenced by the stated interest of key stakeholders in the planning and heritage management sectors in Edinburgh.

Although Canongate is included in the Edinburgh Old Town and New Town World Heritage site, the ex-gasworks area does not have any formal heritage designation. However, due to its location, the redevelopment of its last upstanding remains at 179a Canongate has the potential to impact on the wider World Heritage site, as well as the setting of surrounding buildings that do have formal heritage designation, including the Old Tolbooth (Category A), the flats backing onto Gladstone Court (Category B and C) and the Kirk and kirkyard (Category A). The site is also overlooked from Calton Hill in the New Town.

With consent already approved for partial demolition of the remaining Gasworks buildings at 179A Canongate, and set against the backdrop of the New Waverley development, our focused value assessment took place alongside significant urban transformations. In doing so, it examines the social values associated with forms of heritage that are in danger of being further fragmented or erased. Canongate is a locus of residence, employment, entertainment, education, and ceremony at the heart of a capital city. As discussed below, it is also associated with one of the city’s more transient and mobile populations. As a result, there are a wide range of individuals and communities with interests in, and attachments to, the area.

Understanding the site

The burgh of Canongate was founded in 1128, when David I granted to the Augustinian Abbey of Holyrood to establish a burgh between the Abbey and Edinburgh. The burgh's expansion reflects its topographic constraints and its original layout is well-preserved today. Furthermore, Canongate, even while constantly developing, preserves buildings and remnants of all the periods, from its medieval origins through to recent regenerations.

These two key aspects of the burgh are reflected in the research area, located on the north side of the historic core of the Canongate and the Royal Mile. Its most important historical phases relate to the industrial and post-industrial era, but medieval and post-medieval traces also survive. As mentioned above, it lies in close proximity to the Tolbooth (dated c. 1591), the administrative focus of the ancient burgh, and the Canongate Kirk (dated c. 1688 - 1690), the religious focus, both Category A Listed Buildings. As in the rest of the burgh, except for the street frontages, the area was used mainly for semi-agricultural purposes up until the early 19th century. The semi-agricultural setting was one of the main reasons why the area was chosen for a new Magdalene Asylum in 1805. The main entrance and front garden of this charitable institution for "fallen women" was located on the site of the current Gladstone Court. A second wider yard extended from the back of the building to Calton Road.

However, the advent of gas production, allowed by an Act of Parliament in 1818, had a strong impact on this area. Whilst initially the industrialisation seemed to follow the pattern of medieval and post-medieval small-scale industries and crafts, during the 19th century the Canongate landscape was heavily affected by the extent of industries' growing operations. The New Street Gasworks is the perfect example of this phenomenon. The first buildings of the Edinburgh Gas Light Company were erected in the 1817, but the Gasworks expanded during the century to fill completely the area between New Street and Old Tolbooth Wynd. The Magdalene Asylum was partly absorbed by the Gasworks after 1864, when the institution was moved as the Canongate area was deemed to have lost its rural and idyllic character. The Gasworks buildings currently located in 179a Canongate were built over the Asylum's front garden, incorporating an adjacent courtyard and structures.

The decline of the Gasworks began in 1881 with the arrival of the electric lighting and the erection of a major new industrial site at Granton in the early 1900. From the start of the century until 1925 the ex-Gasworks site in New Street became a popular football ground, the Bathgate Park, a cinder pitch that drew large crowds. It was used for matches, but also for band concerts and other sports. However, the site was sold to the Scottish Motor Transport Company and a bus depot was constructed there in 1928. This was extended in the following years, and turned into a large car park in the 1990s. Between 1996 and 2003, the Out of the Blue arts charity (https://outoftheblue.org.uk/) converted some of the derelict bus garage offices into an arts centre, providing a workplace for artists and organisations, but also a space for live performance and club nights at the Bongo Club. The car park and the arts centre were demolished in 2006 and the area is part of the New Waverley masterplan redevelopment.

In contrast, the remains of the Gasworks at Gladstone Court are still standing on site. The complex has been altered over the years and used for different purposes. In the late 80s it was converted into office accommodation, and partially extended. Between 1970 and 1980, it was used as one of the venues of the Richard Demarco Galleries, hosting Avant Garde exhibitions and activities (https://www.demarco-archive.ac.uk). Most recently (2018-2019), the buildings hosted one of the most popular indie markets in Edinburgh, the Old Tolbooth Market, a daily market originally set up as an experimental community arts and work project (https://oldtolboothmarket.com/). Since the Market closed at the end of 2019, the site has been empty, awaiting commencement of an approved redevelopment. There is currently no public access to the interior of the site.

TOOLS AND METHODS APPLIED

Offline and Online

Architectural Level

KEY FINDINGS

The findings from each method are presented separately.

Contemporary social values and responses to historic urban transformation

The site at 179a Canongate is valued in part as a ‘public’ space contributing to the sense of a community and place, even though it has never been in community ownership. Throughout its recent (20th and 21st century) history, the site has had a variety of public facing uses that served both residents and people coming into the area for entertainment or work. These public uses were described as bringing “animation” to the area. The memories people shared of the Canongate were also often associated with communal activities, whether at key times of the year (such as people congregating in the street at New Year), playing in the Wynds and Closes as children, shopping in the markets or attending the various clubs and music venues in the area. The redevelopment and anticipated change in use was of concern and viewed as part of a wider trend towards the privatisation of what was once public space and public housing. This kind of tension, between local communities wanting to protect public uses of the area and competing private interests, is a long-standing one in Canongate, pointing to a recurring disconnect between regional governance and local stakeholders.

The value of the case study site as working people’s heritage was more prominent online (especially through Facebook and Flickr) than in the offline investigation. People remembered the case study area for the heritage associated with their working lives or those of others they knew. Discussing known figures and shared experiences, the comments alluded to the extensive memories and significance of the site’s recent history to residents and workers past and present. It was also possible to identify a strong nostalgic attachment in these posts to the historic buildings and their uses.

The relative scarcity of public space in the area and opportunities for people to come together means that local communities are somewhat ‘hidden’. However, there are a wide range of users and communities with interests in the case study area, including a clearly articulated community of location, residents with multi-generational connections to the Canongate, and other communities that connect with the historic and present-day diversity of the Canongate. The diversity of communities for whom Edinburgh and the Canongate are and have been home is potentially elided by a focus on particular periods (in particular the medieval old town) and the national Scottish story in the preservation and presentation of the built environment.

Both the UNESCO World Heritage statement of OUV and local residents recognise the tensions in maintaining the integrity of the Old Town within a modern, living city. Many offline respondents who lived locally expressed a sense of pride at living in a city that attracts visitors from all over the world. However, while people recognised the importance of tourism to the local economy, there was a tension between the emphasis on Canongate as a place to visit vs a place to live. Interviewees made references to visitors or transient populations not sharing the sense of “ownership” or “respect” for the area that longer term or more settled residents feel. Linked to the points above on the ‘hidden’ communities living in the area, the gradual loss of local amenities in the Canongate (such as independent shops catering for residents’ needs) was a frequent concern, aligned with online posts expressing a preference for local and more ‘genuine’ cafés compared to big chains and "city-museum" urban regeneration. These responses highlight that it is not only the appearance of the area but the lived experience of the place that is important.

Although not all the past phases of the site were initially known to online survey respondents, 64% ranked the Magdalene Asylum as either the 1st or 2nd preferred aspect of the site to be conserved, with 56% ranking the Gasworks as either the 1st or 2nd to be conserved. From answers provided by those who ranked the Asylum highly two major themes emerged. First, the asylum was frequently seen as the most “historical”, in need of protection as a result of being the oldest and therefore most “important” aspect of the site, suggesting that time-depth itself added value to the site. Second was the significance of remembering Scottish women’s history and the difficult heritage of their internment. Unease about this heritage, linked to the need not to forget its negative aspects, played out in the responses, as did views on the contemporary issues women face and that women remain marginalised in Edinburgh’s heritage narratives. The offline methods, in contrast, highlighted that familial connections were more important to the values associated with the site than specific aspects of its history. Nevertheless, for several interviewees, the sense of time depth was an additional source of value. People who had recently worked at the site also spoke of their interest in the history of the buildings and of having speculated with colleagues about the past uses of historical features (such as the cellars), as well as engaging in discussions with residents and patrons on its future use.

The material transformations of Building 179a Canongate

forthcoming

HERITAGE AND PLANNING IMPLICATIONS

Rapid urban development can result in fragmentation of both urban heritage and local resident communities making them hard to identify/access. Additional care needs to be taken in such contexts to make sure that resident communities do not get marginalised or excluded from processes involved in planning urban transformation and the heritage futures of deep cities. The timing of assessments of people’s values in relation to the planning cycle are also important. In this case the specific site (the remains of the Gasworks at 179a Canongate) had been out of use for almost two years. Business owners, users, performers and audiences were simply no longer present at the site and proved difficult to track down for the purposes of exploring social memories and oral histories. In such situations, perseverance and a flexible approach can pay off, but identification of participants and relationship building takes time. Online research, including past social media content, is particularly insightful and productive in revealing values and attitudes associated with earlier phases in the development cycle. We therefore recommend this strand of research especially in cases when planning processes are in advanced stages and decisions have already been finalised.

Online methods also proved very productive for facilitating access to a wider range of communities of attachment to and interest in Canongate and the case study site. Researching social media content relating to this case study revealed the importance of the area for people who have family connections with it, people who worked there, people who visited for entertainment and leisure, and people who have an active interest in the heritage of the area. However, many of the offline participants indicated that they did not actively engage in online spaces associated with the specific site or the area of Canongate more generally. This demonstrates the importance of combining offline and online methods in order to access a wide range of different constituencies and associated meanings and values. This is particularly important in a complex urban environment where both tangible and intangible heritage has become fragmented through a series of planning decisions over time, such as we found in Canongate.

Despite this fragmentation, the research methods revealed myriad values associated with the case study site and the wider Canongate area. Some of these values are associated with the experience of the area as lived space by residents and people who work there (currently or in living memory). For these constituencies, heritage is an important aspect of place-making, but often implicit and tied to use values, as well as broad awareness of the historic atmosphere of the place. Both the offline and online methods identified a perhaps previously under-appreciated interest in the specific history of the site and recognition of the complexity of Canongate, as part of a city with a rich medieval to modern and recent past. These values, associated with the particular histories of the place, the people who had lived and worked there, and the uses that the area had in the past, have the potential for to connect people in the present, through shared experiences and understandings of the site.

Contested values and tensions surrounding change often relate to increased privatisation of urban space, alongside loss of historic features and places associated with public discourses, activities and dwelling places. Places that animated social life in the area of 179a Canongate include more obvious heritage places like Canongate Kirkyard along with the historic Wynds and Closes. However, the ‘public’ sphere is also extended in people’s memories to privately-owned spaces, such as clubs and performance venues, in and around the site of the Gasworks after it went out of use. These rapidly become an important part of the heritage of place, the significance of which is reinforced when the interests of development and regional/national infrastructures appear to be privileged over people’s desire for communal spaces.

Together, these findings emphasise the need to conceive of preservation beyond fragments and architectural facades. It is vital that not just a sense of pastness or disconnected elements of buildings relating to different past phases are preserved, but that the functions of these elements are visible and clearly communicated. Multi-layered preservation that captures meanings associated with past uses or symbolic associations may reduce tension, invite heritage connections between people, and sustain the character and use of a site within local communities.

Canongate case study Further Readings

Jones S., Bonacchi C., Robson E., Broccoli E., Hiscock A., Biondi A., Nucciotti M., Guttormsen T.S., Fouseki k., Díaz-Andreu M., Assessing the dynamic social values of the ‘deep city’: an integrated methodology combining online and offline approaches, Progress in Planning, Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2024.100852

Bonacchi, C., Jones, S., Broccoli, E., Hiscock, A. and Robson, E. (2023) Researching heritage values in social media environments: understanding variabilities and (in)visibilities, International Journal of Heritage Studies: https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2023.2231919

Last update

20.05.2024