Woolwich Key Findings

The findings from each method are presented separately.

Contemporary social values and responses to historic urban transformation:

The social values research took as a focal point the Royal Arsenal Gatehouse in Beresford Square but included connections and associations with the wider area. The Gatehouse occupies a liminal space of connection and dislocation. As the main entrance to the Royal Arsenal, it defined the transition between civilian and military areas, the latter not being spaces that, historically, townspeople were encouraged to feel they had ownership over or belonged. With the rerouting of the Plumstead Road and the redevelopment of the Royal Arsenal site with housing and civic spaces, this sense of separation has in some cases remained. Several respondents (professionals and local residents) expressed a concern that the historical and physical barriers between the Royal Arsenal redevelopment and the town are maintaining a separation between the areas and the residents. The Gatehouse is somewhat detached from community practices and understandings of place, as well as from its original physical context as part of the Royal Arsenal. In this sense it could be said to be a place of disconnection.

For such a prominent building (the Gatehouse occupies the entire North-East end of Beresford Square) it was notable that people did not speak of it as particularly significant – whether architecturally, in contrast to awareness of buildings on Powis Street, or socially. There is perhaps an ‘everyday’ aspect to the building, in the sense that it is familiar, obvious, and not seen as requiring explanation but, in the offline research, attention was more often directed to the market stalls, the two pubs in Beresford Square, or towards the town centre. Research online (the Flickr collection) mirrors this view. The Gatehouse is rarely the dominant subject in photos, and it is always just part of the landscape of the Square. There is also a silence/ambivalence among many communities (all those engaged as part of this study) regarding the Gatehouse as part of the military heritage of Woolwich. This heritage is very prominent within the Royal Arsenal development, but less visible in the town. There was also a sense that the physical fragmentation that followed the closure of the military/industrial area and redevelopment of the cityscape was resulting in a fragmenting of place and communities, with some people being ‘pushed out’.

However, the Gatehouse is also seen as a place of reconnection by some; a place for reconnecting with the past and exercising an identity-making function. There was a suggestion that the Gatehouse (as a result of its dislocation from its original context) is seen somewhat differently to the rest of the conserved buildings on the Royal Arsenal and, as a fragment, is available to be remade in other ways – as part of the town rather than the military complex. The military history of Woolwich is emphasised in the Arsenal development (on signage, in public monuments, and official interpretation) but is far less visible in the town itself; while the on-going military presence in Woolwich is in many ways hidden in plain sight. While acknowledging that for families with a military connection this history may have greater significance, more broadly, community narratives of belonging and place are rooted in shared experiences (across generations and between cultures) and in the historically working-class nature of the area, including the labour and co-operative movements.

People express strong connections to the built heritage of the town centre, which is appreciated for its aesthetic attributes. However, the past and present uses of these spaces are also important, bringing a depth of vision and knowledge of place. Concerns about preservation were linked to remembering the past uses and enabling the reuse of buildings and public spaces – whether as housing, businesses, or places of day-to-day experiences. Development/planning concerns relate to the lived sense of place and what Woolwich is like as a dwelling place (a transport hub but not just a dormitory) that attracts visitors while investing in and leveraging the unique attributes and diversity of existing communities, small businesses, and the built environment.

Systems Dynamics: The dynamic transformation of Beresford Square and its market

An in-depth study of the morphological change on Beresford Square as recorded in the Survey of London and further complemented with information extrapolated from old images and testimonials, has unveiled some interesting features of the Square which in a way define its ‘deep values’. However, these features have been constantly neglected in re-landscaping schemes that have been taking place since the 1980s as a means to revive the Square and its market.

This ‘open space’, currently known as Beresford Square, evolved organically into a public space that hosted an initially ‘illegal’ market that eventually became ‘legal’ in 1879. Attempts to ‘regulate’ the Square and its markets have been continuous since then. Indeed, the Square has been marked by a continuous ‘tension’ between the respective authorities in each period to ‘regulate’ and ‘put an order’ to the open space by endeavouring to attribute a ‘rectangular shape’ to the space through the demolition of the small number of houses and pubs that were built back in the early 19th century, and the communities that resisted this regularization process. The Square and its market have been characterized by a sense of ‘randomness’, ‘irregularity’, ‘informality’ and ‘disorder’ which was further exacerbated by the inclusion of trams and buses crossing the Square amidst market stalls and thousands of Royal Arsenal workers or just residents doing their shopping.

This is an additional ‘deep feature’ of the Square. Beresford Square has been functioning for years as the ‘passing-by’ or ‘connecting point’ between the Town Centre, the Royal Arsenal and the rest of Woolwich. As aforementioned, trams and buses were cutting through the Square amidst hundreds of stalls and thousands of people. In 1984, the widening of the Plumstead Road intended, partially, to reroute the buses in order to provide a safer environment on the Square, seemed to constitute one of the key – if not the main one – drivers of decline that the Square and its market have since been experiencing. The character of the place, which evolved organically in a grassroots manner, was rapidly transformed by the Plumstead Road project. The Square stopped being the connecting point or the ‘passing-by’ point, numbers of market traders started declining, and whole families of traders started disappearing. In a way, it could be argued, that understanding the ‘deep transformation’ of a place – in this case that of the Beresford Square – is equal to understanding its ‘deep values’ which cannot always be evident through material traces.

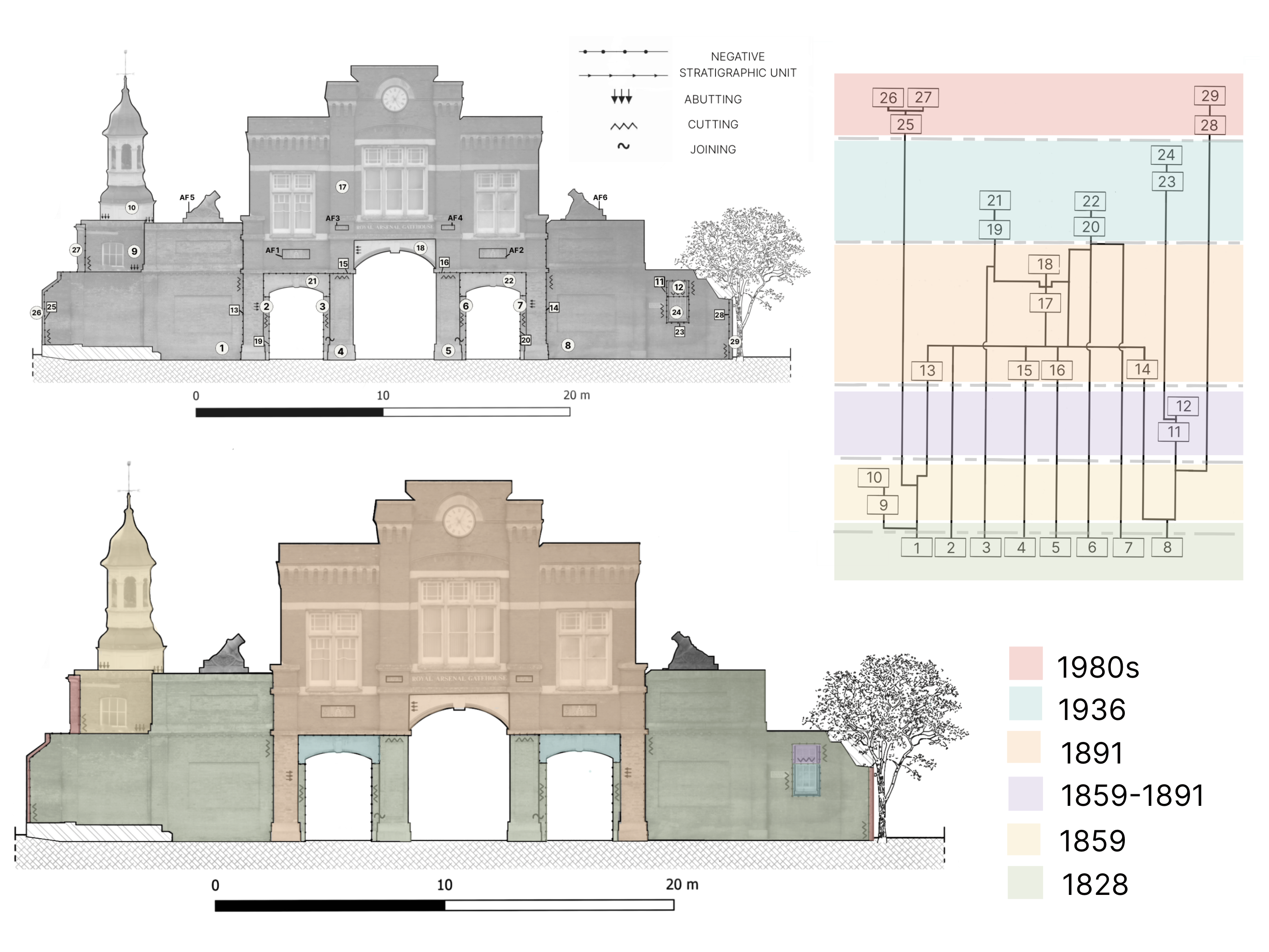

The material transformations of Beresford Gate

According to the cartographic and iconographic sources (old paintings, architectural sketches, historical photographs), the analysis of the south elevation of the front of the gate facing the square evidenced five main transformations phases of the building, dating from 1828 to the 1990s. Some of these detected phases clearly evidenced that the gate is a tangible witness of the material and social changes of Beresford Square, and the whole Woolwich area, further supporting its preservation. It should be noted here that the other front elevations revealed additional phases of the gate’s individual history which are still subject to analysis.

In detail, Phase 1 represents the date the gate was built (i.e., 1828) following the clearances of cottages in town to open-up of the road to the Arsenal. This first gateway in plain yellow-stock brick is clearly recognisable today, the lower floor of the present building, even if some alterations were made to adapt the later additions.

With the demolition of the walls in the 1980s (Phase 5), the ‘inside-outside’ irrevocably changed. However, even if these two spheres materially disappeared, the isolated gate, framed within other relevant urban transformations following the closure of the Arsenal and the rerouting through Plumstead Road, seems to still represent for some people a symbol of physical, social and symbolic disconnection.

Back to the Woolwich Case Study main page

Last update

12.02.2024